.

Why do news reports continue to use “history of mental health problems” as if it’s a complete answer to the “why?” of violent crime? It isn’t.

.

.

.

.

Why do news reports continue to use “history of mental health problems” as if it’s a complete answer to the “why?” of violent crime? It isn’t.

.

.

.

Some thoughts on the difference between how a diagnosis of serious illness is delivered in physical healthcare and mental health care:

.

.

.

.

Some thoughts on that Eurovision straitjacket ‘joke’ and on ridiculing and demonising folks with serious mental health problems for fun and profit in front of 200 million people.

.

.

.

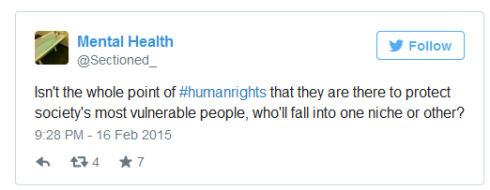

When a human rights story is in the news, you’ll see me banging on about it on twitter and asking where the coverage of the human rights of mental health folks is. I’ll ask why human rights organisations don’t seem interested in this group of people, who can in many cases genuinely be classed as some of society’s most marginalised and vulnerable: sometimes locked up behind closed doors, often out of sight, with little credibilty and subject to state powers to impose forced treatment on people even when they have mental cacpacity. Why don’t we hear about that all day and all night from human rights organisations?

This silence from human rights groups is puzzling when mental health issues are receiving more publicity and prominence and where there is so very much for human rights groups to get their teeth into. That leads me to ask all sorts of questions. For instance:

I’ll ask why human rights organisations don’t seem to be interested in a brand new developing area of rights, namely those under the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) which has been described as a paradigm shift in disability rights. Don’t they want to get in on the action on this hot new area, rather than sticking doggedly with familiar human rights aspects? Are human rights organisations bound to stay in the familiar niches they’ve carved for themselves, or will they look further afield?

I’ll ask whether human rights organisation are looking at the fact that the UK is the very first country to be investigated by the United Nations for violations of the human rights of disabled people under the CRPD. Doesn’t that sound like an interesting and important human rights topic?

I’ll ask what human rights organisations are doing about the brand new section at the front of the new Code of Practice to the Mental Health Act on … human rights. Isn’t it significant – something of note, something to promite – that the new CoP has at its very beginning a brand new section on human rights? I think so. Is it only me?

Are human rights organisations interested in the human rights-based approach all Care Quality Commission inspectors are to take to inspecting hospitals and other healthcare facilities?

Do they take an interest in the recent NICE guidance that all NHS hospitals should prevent smoking on their premises, even in the case of detained patients without leave and are there no human rights implications of that blanket policy (spoiler: yes)? And what of the blanket policies of some hospitals to remove patient phones or prohibit them from accessing social media whilst on ward?

Forced medication is used on some psychiatric wards as a matter of routine, as a first resort rather than a last resort, even when people have the mental capacity to make medication decisions for themselves. Aren’t the human rights of people subjected to forced medication in psychiatric detention of interest to human rights groups?

Voting rights are meat and drink for human rights organisations. So why no campaigns or even interest in the voting righs of people with mental health problems?

Why is it? Why don’t human rights groups take an interest in those topics when there’s so much for them to get their teeth into and when mental health is such a hot topic at the moment, often in the news?

Mental health folks don’t seem to get a mention – unless we fall into an existing favoured category such as prisoners, death row inmates or deaths in custody

When I see human rights organisations talking about human rights, I notice time and again that, whilst all sorts of different niche groups and causes are trumpeted, mental health folks just don’t seem to get a mention – unless, that is, we fall into an existing favoured category, such as people in detention in prison or on death row, or deaths in custody. Why is that? And what – given important developments in human rights and current social and political changes giving mental health much more prominence – can be done to get violations of the human rights of mental health folks more of a focus and the enforcement of the human rights of mental health folks made into more of a priority?

Why am I told mental health folks are “too speciailst” when all sorts of other specialist groups are chosen for human rights campaigns?

I’ve tried to follow up with various human rights organisations to find out about the work they do on the human rights of mental health folks. I’ve tried. However, I’ve typically been ignored or, when I do get a response, I’m fobbed off with the line that people with mental health problems are a niche group that’s “too specialised” for them. This doesn’t seem to accord with campaigns run in respect of other “niche groups”, such as refugees, prisoners, LGBT people, trades union members, military personnel. Not at all. And it goes against the premise that human rights are most needed by those people who are most vulnerable – and people with mental health problems can be in very vulnerable postions. It’s niche groups who most need human rights.

Why the seeming lack of interest from human rights organisations? Why are people with mental health problems being marginalised, even by those organisations and individuals who purport to champion society’s most marginalised and vulnerable people? Why – at a time of expanding human rights provisions for people with disabilities including mental health problems, at a time of increasing promimence for mental health issues growth, development and prominence of issues surrounding people with mental health problems – why are human rights organisations not swinging into action and grasping the opportunties available to do good, high profile work and make a real difference to the lives of mental health folks?

Why the seeming lack of interest from human rights organisations? Why are people with mental health problems being marginalised, even by those organisations and individuals who purport to champion society’s most marginalised and vulnerable people? Why – at a time of expanding human rights provisions for people with disabilities including mental health problems, at a time of increasing promimence for mental health issues growth, development and prominence of issues surrounding people with mental health problems – why are human rights organisations not swinging into action and grasping the opportunties available to do good, high profile work and make a real difference to the lives of mental health folks?

Could it be that human rights organisations are simply prey to the same ol’ same ol’ stigma and discrimination that blights the lives of mental health folks every day? Is it a case of priorities and people managing mental health problems just aren’t as important as other groups – even though we make up such a large minority of the population? I’m still trying to find an answer.

I’ll keep on trying. The human rights of people managing mental health conditions are too important to overlook.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Earlier this evening, I had a fascinating conversation with a relative who’d trained as a learning disability nurse in the 1960s. She shared her memories as a nurse, visitor and patient at Coldeast Mental Deficiency Colony, Littlemore Asylum, Digby, Langdon, Tone Vale and other hospitals.She had some interesting observations on the differences between the old asylums and modern psychiatric hospitals. It was hard to tell if it was pensioner nostalgia or if things really were, on balance, much better in the old asylums. But that was her clear view.

She spoke about the old asylums, on the outskirts of town, each having a home farm where patients would work, have a purpose, be outside and contribute to the life of the institution. Of patients cleaning the wards, nurses helping too, of real hands-on nursing, of vocation, of the matron closely supervising the ward, of strict hygiene standards that meant, for instance, never sitting on a patient’s bed. Of food cooked on the wards, and nurses trained in cooking too in case there was no one else there to do it. Of the value of good routine, of having to boil the needles and bandages, of having to manage patients without drugs, of highly-trained staff.

She spoke of parents being persuaded to abandon their ‘mentally retarded’ children, to leave them behind and get on with their lives. Of how wrong that was and of how people could contribute so much to society if they had routine jobs. That seemed her one regret from those times.

She spoke of nurses needing to get at least two years’ experience before they could go on the wards with the more difficult patients. Of how patients would be matched to particular nurses, as some patients could be violent from time to time and you had to know how to relate to them. Of how the experienced staff, strict routine and a pride in their work created a secure and stable environment for patients and staff alike.

And she spoke of how things had started to ‘go down the pan’ in the 1970s when, for the first time, staff could use drugs to ‘keep patients quiet’. Of how younger staff were recruited, how routine slipped, how patients were left to do as they wanted, neglected and ‘drugged up to their eyeballs’. Of seeing the nurses’ pride in their job dwindling, of staff having affairs with each other, of hygiene standards slipping. She’d seen this in residential and nursing homes too: residents drugged to keep them quiet, one perhaps two staff on overnight, and little care.

And then she compared her time working in the old institutions with her recent experience of care in a brand new psychiatric hospital. She said, when she was a patient herself, the staff were ignorant about mental health, and some nurses were ‘really nasty’. Staff congregated in cliques or in the staff room. They didn’t mix – ie care for – patients. At night, nurses would be on their smart phones and would brush her away when she tried to talk to them. Of how the ward phone was kept locked in the nurses’ office, so patients couldn’t contact the outside world except with staff permission. (That’s a recipe for abuse behind closed doors, if ever there was one.)

She spoke of there being no facilities for exercise – and, when she went in, she was used to walking miles. How she got fatter & fatter. That there was a small internal courtyard but she wasn’t allowed in it in case she ‘climbed over the wall’ and escaped. How she was finally, after several weeks, allowed into the courtyard and would then walk round and round and round. How there was a swimming pool and gym elsewhere on the hospital site, but the nurses wouldn’t take her there. How she badly missed activity. How she came out of hospital far more unhealthy than when she went in, physically.

How nursing had become more technical, and nurses had more status now, but had lost the basic hands-on skills. How nurses nowadays had lower hygiene standards and no idea about cross-infection control. How hospitals needed highly-trained staff but how the staff who’d treated her didn’t have sufficient training. How nursing was just a job now, not a vocation.

It was fascinating listening to her experiences as staff, visitor and laterly patient starting in the 1960s and running right through to the present day, and the comparisons she made.

.

.

.

.

.

Related links:

.

.

.

Another post where I’ve set out my thoughts in tweets and hope to write it up into a blog post but, in the meantime, here are the tweets:

.

.

.

.

.

.

Related links (in date order):

.

.

.

How’s your day been? That’s a question you’ve probably asked many times, and been asked a fair few too. It’s part of the normal everyday engagement between people that oils the social wheels. Often it’s not a genuine enquiry in the sense that a detailed response is not expected: instead, it’s a baton being passed, with you expected to pass it back and say, “Fine thanks. How about you?” That “fine” can mask a lot of days that aren’t fine, whether better or worse, but we’re all expected to join in the general cheerleading, pretending to be “fine” too.

For people struggling with mental health problems or managing a long-term mental health condition, how our day has been is probably a bit of a mystery to the general public. This can be a source of assumptions, stereotypes and prejudice, whether that’s the “lazy faker” of depression who just needs to take themselves in hand and go for a brisk walk; or the “dangerous maniac” of schizophrenia who should be monitored and contained for public safety. These prejudices and stereotypes can feed into self-stigma that brings about a sense of isolation.

Our daily lives are also likely to be a bit of a mystery to the professionals who provide our care, whether that’s a therapist an hour a week, 20 minutes with a psychiatrist every 3 months or 10 minutes with a GP every few weeks. What it’s actually like to live with a mental health problem can be pretty uncharted territory unless you’re doing it yourself or living with someone who is. There’s so much more to good mental health, and to good mental health services and support, than the NHS, drugs and talking treatments. People just like me are out there, living our lives, quietly getting on with things day to day, and there’s a new project that aims to capture that reality. It’s called A Day in the Life.

A Day in the Life (the mental health project, not the Beatles song) asks people with mental health problems to share what their day has been like – and what has helped or made the day worse – on four set days over a year.

The project aims to shine a light on the everyday lives of people with mental health problems to raise awareness and to help the general public better gain a better understanding: to challenge myths and bust some stigma. It also aims to get people who may never have blogged before writing about how their day went – and perhaps then finding an online voice they never knew they had. There’s guidance on how beginner bloggers can start writing.

But another objective – and the reason the project is funded by Public Health England – is to help policy-makers understand what makes a difference – good or bad – to the lives of people with mental health problems. Although not a scientific study, the project will provide an insight to help influence policy decisions on services provided in future. The online snapshot diaries will also help to highlight emerging themes and suggest future areas for investigation.

I’ve signed up to take part in the project and have already posted my entry for the first day, Friday 7th November. The remaining three days will be in winter, spring and summer 2015.

Follow the project on twitter using hashtag #DayInTheLifeMH and scroll down to find out more about the project and how you can take part.

.

Below is my entry for 7th November, which will appear on the Day in the Life website when everyone’s contributions so far – totalling around 370 – go live on Monday 17th.

Please note: I chose to speak very candidly about what I experienced that day, so please read with care if you’ve been affected by suicide, suicidal thoughts or depression – or simply scroll down to the bottom where you’ll find useful links.

.

.

I’m on Twitter – a lot! So, as usual, after turning off my alarm, the first thing I did this morning was to check what tweeps I follow had posted, to catch up on news in the mental health world. Then, returning to bed with breakfast and my pet, as it was the last day to sign up to #ADayintheLifeMH, I sent out a series of tweets to encourage as many people as possible to sign up. The more sign-ups, the more varied a picture of living with mental health problems it will provide.

Next, I checked what had been happening on the #SamaritansRadar hashtag. Samaritans Radar was launched by the Samaritans in October and, ironically, had had a disastrous impact on the Twitter mental health community. Numerous tweeps had contacted the Samaritans by Twitter, email, phone and letter to beg them to take the secret automated surveillance and alert app offline. Experts in various different professions had written about legal and ethical concerns. Mental health experts by experience had blogged about their pain and distress. There was an online petition, an investigation by the Information Commission and even a group proposing legal action against the Samaritans. I was involved in the campaign to have the app taken offline till it could be made safe.

On checking Twitter, it was clear that the outcry was continuing. And the Samaritans had tweeted their followers about A Day in The Life Mental Health!

Next, I tried to work on a blog post about the app. The powerful psychiatric medications I take have an impact on motivation, focus and concentration and, since I’d started taking them, I couldn’t quite connect the dots. It was cripplingly frustrating and is one reason I spend so much time on Twitter: 140 characters just about matches my attention span! Being sedated so your higher functions no longer work properly makes it hard to manage a home and get everyday tasks done, let alone get anywhere near organising your own healthcare in a system that relies on people being pushy. Being a sedated blob doesn’t get you very far and is one reason I haven’t been able to get proper treatment for myself over 3 years since I was discharged from hospital. Here I am, still parked on welfare benefits.

I struggled for a while to try to gather together my thoughts on Radar down on paper, but was unable to do so. I tried to make an overdue phone call, but couldn’t. So I had lunch, then caught the bus to a medical appointment.

Later, as I walked back through a tree-lined park on a beautiful autumn afternoon listening to the radio, I heard a trailer for this evening’s BBC Radio 4 Any Questions saying that one of the topics the panel would discuss was the Assisted Dying Bill. This caused my own “suicide radar” to go off.

Ever since getting notice of eviction from my home so my landlord could sell it (2 months’ notice, out of the blue, after over a decade), I’d been tipped into a deep, debilitating depression. At times, I was utterly tortured by suicidal thoughts. My home had been my security and stability and now I was losing that. And the awful Radar app had thrown a spotlight on suicide, meaning my Twitter feed was full of intellectual suicide talk.

Suicide was being discussed as a fascinating concept, rather than what it was to me and many other mental health folks using twitter: a very real mental pain we were struggling with at that very moment. At times, it seems as if there’s a part of my mind monitoring everything just in case it might be useful in some way in despatching myself – my own “suicide radar”. That’s why the Assisted Suicide Bill caught my attention. Being able to die with dignity alongside friends and family – rather than experience years of unalleviated suffering or go for a secret and uncertain DIY method – was an option I’d like to have available too.

I’ve had thoughts about suicide in all sorts of places, with all sorts of people and whilst doing all sorts of things. Sometimes I’ll be plagued by all-consuming thoughts of suicide; other times they’d be a background hum, like a reflex response to every turn of events, a mental tic; and sometimes, as today, there’d be calm planning. These thoughts were going through my mind as I walked through the warm autumn afternoon, kicking up piles of fallen leaves. No-one looking at me would have known.

Back home, I checked Twitter again. At 6pm, the Samaritans tweeted to say that, after 10 days of uproar, the Radar app had been suspended! It was a begrudging statement which did not acknowledge the distress the app had caused, and the so-called apology was an example of how not to apologise. But, nevertheless, the announcement meant that mental health folks could sleep easier in their beds over the weekend. I continue to feel uneasy as to what “suspension” means in practice. Whilst no-one doubts the app was developed with good intensions, the way it was imposed on everyone had damaged trust in the Samaritans.

I spent the evening debating with people on Twitter about Samaritans Radar, listening to Any Questions, then retiring to bed to read Everyday Medical Ethics and Law. It didn’t use to be my sort of book at all, but that was before I was unlawfully arrested, sectioned, held in seclusion and treated by force. Nowadays, chapters on patient autonomy and choice and how they are glibly brushed aside for mental health patients concern me deeply.

Sadly, lack of concentration scuppered my attempts to read the book – so it was back to Twitter.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

Related links:

.

.

.

It’s okay to ask for help, as today’s Mind charity tweet says. However, it is NOT okay to have to ask again and again and still not get appropriate and timely help – or any help at all.

Thoughts exploring the theme of lack of actual help available for mental health problems, whether or not you’re able to ask.

(To be expanded into a written blog post when I have time.)

.

.

.

You know the stereotype: the “mad axe-murderer” or “deranged maniac” who appear in the media in the extremely rare and therefore newsworthy instances where someone with serious mental illness commits a violent crime. I wrote recently about how the “unpredictable and potentially dangerous” stereotype is so accepted that it goes unnoticed, assumed to be a natural fact; how it is therefore repeated, and reinforces negative assumptions about those of us managing mental health problems in our daily lives. Almost goes unnoticed, that is, because I for one do challenge outrageously stigmatising and inaccurate stereotypes about mental ill-health when I see them. I say this sort of thing:

Yesterday, I was asked by Sean Jones QC to put my money where my mouth was and come up with research links to dispel his “murderous psychosis” stereotype that I’d just challenged. How did I know that these statements, which all contradict the stereotypical media portrayal of people with mental health problems, are true? How could I prove these points to someone who wants to know – or at least give them sufficient information so that they can go away, do their own checking and make an informed judgment for themselves?

When someone asks me what my proof is that the “murderous psychosis” stereotype is untrue, I usually refer them to organisations like Time to Change, Mind and Rethink Mental Illness. In other words, experts; organisations that make it their full-time business to know what’s what in the field of mental health.

Both are a good starting point. However, they may not satisfy someone who wants to drill down into the details themselves. Of course they could contact those organisations direct themselves, but what can I do to help? What else is there, if you want to dig a little further? Here are some more links I send to people:

Here’s more about psychosis and on still being human whilst having serious mental health problems:

These are all good places to start. But where else might I point people to? I’m good in 140 characters – but that’s about it. I’ve retweeted interesting studies when I’ve randomly stumbled across them, and that’s how I’ve formed my views. I’m not a mental health researcher. I’m not even organised. I don’t have access to scientific reviews behind pay walls. I haven’t been collating a database of relevant research – unless you count my list of favourites on twitter (currently running to over 2,000).

New research is published all the time but the general public (including me) will mostly only have access to press reports on the research, which typically highlight some juicy aspect to ‘sell’ the story to potential readers. I’ve also noticed that not all research is particularly good quality: sometimes research seems to ask the wrong questions; some studies look at just criminals or just people with psychosis, rather than looking at the whole population. Mostly it seems research conflates cause and correlation, simply counting violent crimes by people with mental health problems when the fact of having a mental health diagnosis (either at the time a violent act was committed or at a later assessment) does not prove that the mental health problem was the cause of the violence. There was a US study I came across that said, in convicted violent criminals with serious mental illness, the mental illness was the cause of the offence in under 7% of cases. It was interesting because it highlighted the difference between having a mental health problem at the time of a crime and that mental health problem having been the cause of the crime. But then I lost the link to the study and haven’t been able to find it since. Like I say, I’m good in 140 characters.

Like plane crashes, “murderous psychosis” makes the headlines because it’s rare. It’s alarmist, inaccurate and causes suffering to people managing mental health problems in our daily lives. There’s ignorance about psychosis & violence, with the media stereotype we’re fed. But, when challenged, some people do want to know more.

.

.

.

.

.

Related links:

.

Update (pieces written or added since publication of this piece):

.

Background links

.

.

.