How is the quality of inpatient mental health care measured? I’m asking a question, because I don’t know the answer and I’d be happy to learn if anyone would like to send me information.

So far as I know, the only nationally-collated and reported statistics for mental health patients are for deaths and self-harm, both of which are physical measures. It’s known that some people coming out of psychiatric hospital have had a difficult time in there, but there doesn’t seem to be much research interest in looking at why that is or how to make patients’ experiences of inpatient mental health care better. Perhaps it’s just part of what seem to be long-standing low expectations of what mental health care can achieve; perhaps it’s just accepted as a natural fact that people will dislike being detained against their will; or perhaps it’s that psychiatric patients are assumed to be a pretty miserable lot by our very nature so it isn’t the role of mental health services to try to show us a good time. I don’t know.

But I do know that I came out of inpatient detention with post-traumatic stress disorder as a direct result of what was done to me behind closed doors. I do know that I have a shoulder injury which I still receive physiotherapy treatment for more than 3 years since it was inflicted on me. And I do know that I want to try to make psychiatric care less traumatic.

To that end, I’m proposing 3 simple measures, modest proposals as a starting point to help shine a light in dark corners, with the aim of uncovering and encouraging best practice and reducing the routine use of harmful practices – a “big data” approach.

Here are my three recommendations for starting to reduce the potential of coercion and forced medication to cause harm:

.

(1) Collate and report national statistics on the use of coercion and forced medication

How is use of forced medication not notifiable? Objectively, it’s physical assault on someone, and at their most vulnerable. It would be grotesque if this were considered to be a routine and natural part of mental health ‘care’. It’s such a gross invasion of a person’s human rights that it can’t be treated as nothing. Individual hospitals may keep records, in their own ways, but there’s no uniform definition of “forced medication” & no central recording. There’s no way to know which hospitals or wards use forced medication most, where best practice is, or where injuries occur at the time or after.

Make it compulsory to record each use of forced and to report it nationally. That way, national statistics and a picture of best practice can emerge as a basis for comparisons and for developing evidenced-based interventions.

Big data is only as good as the input it’s based on, which will necessitate developing standard definitions of coercion and forced medication, to include:

-

Where force or some other form of coercion is mentioned to a patient in order to coerce them to take medication “voluntarily”.

There was a nurse on the ward where I was detained who seemed to be able to find out what patients were most afraid of then threaten them with that in order to get them to comply. In front of me he threatened one friend, who’d been moved from another ward after having been assaulted by another patient, with being sent back there if she didn’t take her medication immediately. Knowing I wanted to be seen to be complying, he twice threatened to report me to the psychiatrist if I was back late from leave.

-

Where the medication “hit squad” (called the rapid response team where I was detained) attends and stands nearby to encourage a patient to take medication “voluntarily”.

That same nurse would call the all-male rapid response team to stand outside the room of a friend whose culture kept men and women largely segregated, in order to “encourage” her to take the prescribed medication immediately. Each time, she would’ve been anxious about taking the medication and simply needed time to settle, but instead staff would become impatient and try to hurry her, making her more anxious.

-

What was done to me, namely the full 6-person take-down).

Even that may need to be spelled out because, for instance, the first time I was forcibly medicated, it states in my notes “No force used” which is simply a lie.

Such definitions will need to be worked on carefully to make it more difficult to fail to record incidents by accident, meaning any failure to record would have to be quite deliberate.

Use of forced medication is such an invasive process – state-sanctioned assault on someone at their most vulnerable – that there cannot be a justification for treating it in such a slapdash way and not even recording it. Make use of forced medication notifiable.

.

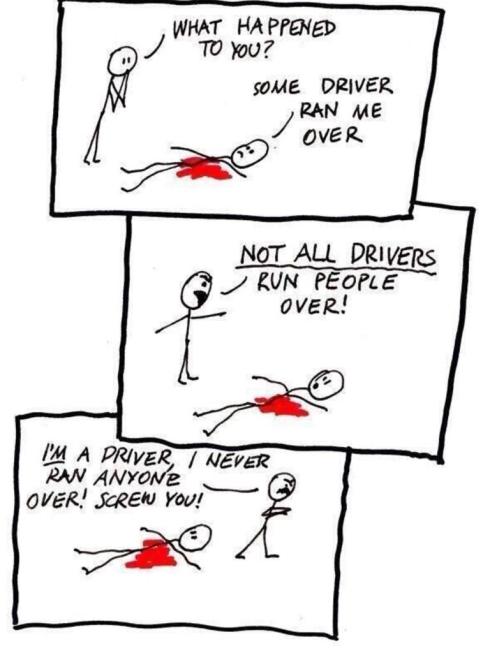

(2) Having to earning the option to use coercion or forced medication

Make the option to use of force something which must be earned, each and every time, by exhausting every alternative option beforehand, each and every time. It may suit some ward staff to go straight for forced medication as a short-cut for the purposes of ward management, but forced treatment can have damaging medium and long term effects. I remember each and every time I was medicated by force, or restrained, or held in seclusion. It is not nothing, especially when you are struggling in mental health crisis. Using force on people at their most vulnerable can cast a long shadow. It should never be a first resort.

In my case, force was the first resort every time. Not once was I offered medication and given the chance to take it voluntarily: instead, I was ambushed and drugged. I never knew when the hit squad would turn up and do it again. Even when my solicitor had advised me that the quickest way to get out of psychiatric hospital was to “comply, cooperate and engage” so I’d been first in the medication queue and had taken medication voluntarily, I was ambushed again by the hit squad the very next day. No warning, no discussion, no chance to comply. Ambushed. Repeatedly.

The Mental Health Act Code of Practice prescribes strict conditions for use of physical restraint, but not so use of forced medication. Perhaps it’s presumed that the general “least restrictive” principle will mean that forced medication will always be used as a last resort but, in my case, it was very much a first resort.

Staff haven’t just “done the right thing” because it’s the right thing to do, so it’s become clear they must be made to do so. Detailed guidance on the prerequisites for use of forced medication (and sanctions for contravention of procedures) are necessary.

.

(3) Debrief patients after each use of forced medication

After each use of forced medication, I’d simply be left, abandoned in dirty sheets. The first time it was done to me, I got up, pulled up my trousers to cover my buttocks then ran down the hall after the departing staff asking them what they’d just injected me with, what it was for, what I could expect to feel, how long it would last – but received no response. They continued walking away down the corridor without responding to me once. Not one of them even so much as turned their heads to acknowledge I was speaking. And in the meantime they chatted away to each other. I was left to return to my bed space feeling confused, humiliated, anxious, violated, not knowing what had been done to me or why or what would happen next. I’d been violated in my bed but had no change of clothes or change of sheets. None of my questions was ever answered. I only learned what drugs had been administered to me when I received a copy of my medical records, months later.

Each time after that, the pattern was the same except that I no longer ran after the staff trying to ask questions but would just be left stunned in my bed space, having been subjected to ambush medication yet again. Left in soiled sheets with my bed pulled out from the wall, having to somehow try to piece together my dignity and try to get some clean sheets and clean clothes, so shocked I’d quietly creep around in slow motion, trying to process what had just been done to me. Shocked again, brutalised again. I think the worst time was the time they came for me even when I’d taken the medication voluntarily; it seemed that nothing I said or did would make them stop.

I learned after coming out of hospital that it’s routine practice for staff to be debriefed after having been involved in a use of forced treatment. Staff are professionals at their place of work, but patients on a psychiatric ward are at our most vulnerable – so why aren’t patients debriefed too? It’s common sense. At the very least, the forced medication process is a very intense experience for people who are poorly, more so than for trained staff who are healthy. It’s clear that forced medication has the potential to harm patients. Good mental health staff want to reduce the harm caused to patients. Let’s do it.

People who choose to train as mental health nurses, occupational therapists, doctors or healthcare assistants don’t for the most part choose their career in order to leave people so traumatised they come out of hospital vowing never to go back into “that place” again, terrified to ask for help, even with post-traumatic stress disorder. Of course, in every profession, there will be a few rogues and, just as professions giving power over children attract sexual predators, so psychiatry will attract some people who want to exert power behind closed doors over vulnerable people who won’t be believed if they speak up about what’s been done to them. People with both good and bad intentions go into mental health services; knowing that to be the case, how can mental health services, especially inpatient wards, be designed so that the good intentions of the former are the most practical option to express but the bad intention of the latter are harder to express? At present it seems that inpatient wards facilitate bullies and brutes, encouraging those who are like that to start with and pushing those who went in with good intentions to become bullies and brutes to or at the very least inured to cruelty and lack of compassion.

In order to challenge endemic use of forced medication, first the evidence of its use must be gathered.

If you’re wondering what I mean by “forced medication”, this’ll give you a flavour:

- Do you remember your first time?

- Treated like an animal

- Restraint: 10 ways it harms psychiatric patients

- Forced medication: resistance is futile

There is no measure of quality of mental health care but, just as statistics for pressure ulcers are gathered as a signal that

something’s going wrong on a physical healthcare ward, so statistics about the use of coercion and forced medication can be used as an indicator that something’s not quite right in mental health care. I don’t know all the healthcare or NHS jargon but comparing use of force in psychiatric care to pressure ulcers, where are the CQUIN goals to reduce use of force? Should each use of force be recorded as a ‘serious incident’? The above are modest recommendations intended to be simple, doable steps to reduce harm to patients of forced medication. How can these steps be brought about? Are there better ones and if so what are they? What needs to be done? What’s the first step in making this a reality? Put your thinking caps on and let me know!

.

.

.

Related links:

.

.

.