Harry Enfield as Kevin the Teenager (PA)

Have you seen this? Rachel Hobbs of mental health charity Rethink Mental Illness asked me this afternoon. She was referring to the charity’s response to a piece in the Sunday Times headed “I’m sorry, he’s not a differently gifted worker – he’s a psycho”. I’d just arrived home so hadn’t but, sadly, I had already seen the piece that prompted the rebuttal – and been shocked to the core.

The Sunday Times piece to which Rethink had issued a response advises employers of the necessity of screening job applicants and employees to weed out undesirable ones. The author writes:

“There are three important questions. The first is how you spot these people at selection so you can reject them … The second is, given that they have already been appointed, how to manage them … Sometimes it is a matter of damage limitation … The third is how to rid your workplace of these maladaptive personalities, and that is the toughest question of all.”

Putting aside for one moment the reference to “maladaptive personalities” and the telltale use of “these people” (a clue that we’re about to experience a group of people being made “other”), this all seems fair enough. After all, what employer wants to end up lumbered with rogues or duffers, or people who are simply not suited to the post being filled?

In any recruitment process, whether to fill a new role or replace a departing employee, some sort of selection process is inevitable. Indeed it is welcome, since it will give both prospective employer and employee the opportunity to see whether post and candidate are a good fit. I’ve read plenty of books and done courses including interview techniques, networking, career development and workplace psychology. I’ve undertaken interviews and assessments. It’s an interesting field and one that can bear fruit for employers and employees.

So what’s the problem? The problem is that the premise of the piece is – regardless of the role to be filled – people fall into two categories: they are either desirable or undesirable in the workplace, and the “unemployables” are to be hunted down and excluded. “These people” are to be avoided at all costs. “These people” have “maladaptive personalities”.

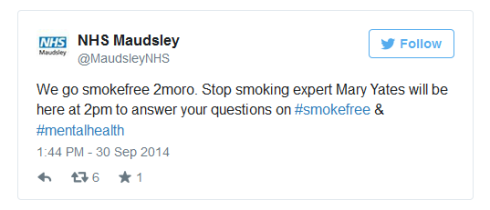

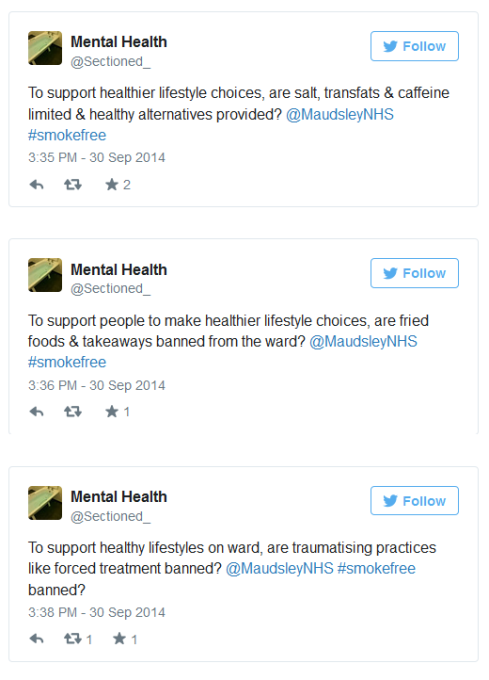

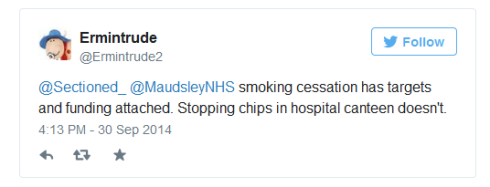

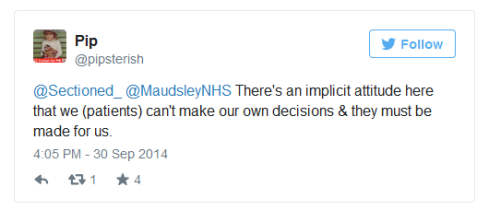

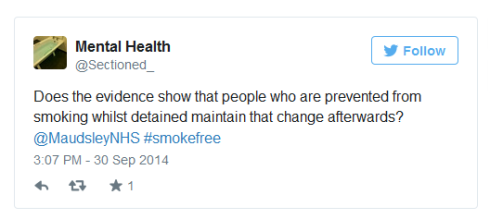

“These people”, according to the piece, fall into 5 categories, namely people who exhibit what is classified as antagonism, disinhibition (Harry Enfield’s Kevin the Teenager – pictured above – is the illustration the author provides for this category), detachment, negative affect or psychoticism (bear with me – this isn’t made up). Each, as described in the piece, has a clear link to mental health problems.

Reading the piece, I had several strong immediate reactions – to the extent I sat down and wrote out my thoughts (then, unhelpfully, lost the piece of paper; perhaps there should be a sixth category of “unemployables”, the abstent-minded).

First, I took away the message that (based on the characteristics of the people described in the 5 categories, some of which I share) I was most definitely not wanted in the workplace. I was not wanted in the workplace and there were armies of workplace psychologists devising tests designed to make jolly sure I wouldn’t be able to sneak in undetected.

It felt as if, when I finally feel able to re-enter the competitive employment market and, were I ever to make it through to a job selection process, there would be a head to head battle. On one side would be the selectors, trying to expose my “maladaptive personality”; and, on the other, me, desperately trying to keep my deficiencies and undesirable characteristics under wraps. Then, in the unlikely event I was able to pull the wool over their eyes and win on that occasion, I would always be at risk of exposure and therefore dismissal. And, even if I started a job mentally healthy but then (for whatever reason – even if it was because too much work was loaded onto me at work, causing unnecessary stress) I became unwell, my employer wouldn’t seek to support me, a valuable employee, through that illness – but instead try to get me out.

I was reminded of the recent disappointment of prospective cabin crew Megan Cox. Notoriously, her offer of a dream job with Emirates Air was withdrawn when she disclosed a past history of depressive illness. In Megan’s case, it was clear that the prospective employer had based their decision on generalisations about depressive illness rather than the individual under consideration. Perhaps they were administering a standardised workplace psychological assessment which sought to weed out the undesirables. Megan Cox was deemed undesirable by Emirates Air. Lucky escape for them that they were able to spot her during the recruitment process. The piece made clear that, similarly, I would be weeded out.

Second, the contents made me want to send the piece to all those people involved in making decisions about the social security support of people who, like me, are managing disabilities, to show them the high barriers we have in getting into employment. Only today, it was reported that Employment and Support Allowance and the Work Programme were costing more than the predecessor welfare benefit Income Support and were getting fewer disabled people back into work. Is it any wonder that a system based around the notion that disabled people are out of work because of a lack of motivation (and incentives – or, rather, penalties) to seek work will fail when the actual barrier is the attitudes of employers – fed by pieces such as these – towards people with disabilities?

Third, having assumed at first glance that the piece was written by a generalist journalist to meet a deadline, I was gobsmacked to find it was written by a professor of psychology. A renowned academic – Professor Adrian Furnham – of a renowned institution – University College London – was the author. It simply did not compute.

So then I did a little reading around the subject on the internet. I discovered that Furnham hadn’t made up terms like “dark traits” or “psychoticism”. No: they were legitimate. These terms came from last year’s new version of the US psychiatric manual (DSM5) and from workplace psychology (for the past couple of years). The meat of the piece seemed to be almost a cut and paste from ideas that would be familiar to people who’d studied the field: nothing new, surprising or out of the ordinary. This wasn’t some rogue piece by a lazy journalist in a hurry: it reflected current thinking in (US) workplace psychology. That was hard to swallow.

However, on reading the piece again, there were some flaws (whether of the author or in the editing) which meant it was skewed to paint a worse picture than US workplace psychology actually seems to do. Thank goodness. For instance, the professor conflates the DSM5’s “maladaptive personality traits” (undesirable characteristics) with “maladaptive personalities” (undesirable people). To confuse a trait with a person is a big leap – and a damaging one for the people on the receiving end of the “undesirables” label. Furnham also conflates mental illness (with references to “disorders” and “pathology”) with personality disorders (he lists the 3 DSM5 clusters) and personality traits. Thankfully, therefore, the piece isn’t an accurate representation of the current state of play. In fact, it’s a bit of a mess.

In addition – as is common with fear-mongering pieces – the particular damage “these people” could do in the workplace is left vague; but the fact that they will cause damage is made plain.

The trouble is, however, that anyone not familiar with the nuances in the field (and that might be your average Sunday Times reader) would easily be expected to come away with the very clear message that people with mental health problems – yes, people like me – should be excluded from the workplace at all costs. And that is a damaging message.

Which leads me to my fourth thought on the topic: I wonder (and I don’t know) whether the piece might breach disability discrimination laws.

Furnham argues for keeping “these people” – people with “maladaptive personalities”, people whose symptoms which, as described, fall within mental health diagnoses such as anxiety, depression and schizophrenia – out of the workplace. My understanding is that, where a condition impacts on someone’s health for 12 months or longer, that counts as a disability and is protected by law. In other words, discriminating against someone in these circumstances counts as disability discrimination.

I’m trying hard to see how advising employers on how to avoid employing or get rid of people with disabilities is any different to advising employers to not employ black people or gay people or women. Whether or not it amounts to disability discrimination, it’s clear it is not good to advocate discrimination in the workplace.

Rethink Mental Illness has been in contact with the author and are hoping to have a piece – written with other mental health charities – published in this weekend’s Sunday Times. Rethink reports that Furnham and colleagues were surprised at the reaction to the piece and believe it has been misinterpreted. It seems to me there is a clear opportunity for a dialogue, and for largely commercially-focused workplace psychologists to gain a greater understanding of the crossover between their work and mental illness and the role they can play in the negative stereotypes.

Until employers are willing to consider job candidates or existing employees as individuals rather than categories based on assumption, the prejudices and assumptions of employers will impact on people managing mental health problems like a form of modern straight jacket.

.

.

The Sunday Times published a letter from Rethink Mental Illness and others on Sunday 22nd; and the following day Furnham wrote to explain, apologise and request that the article be withdrawn. Constructive engagement and a willingness to engage produced a positive result.

The Sunday Times published a letter from Rethink Mental Illness and others on Sunday 22nd; and the following day Furnham wrote to explain, apologise and request that the article be withdrawn. Constructive engagement and a willingness to engage produced a positive result.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The Sunday Times story and rebuttal:

.

Employment and Support Allowance

.

Emirates Air and depression

.

.

Here’s the full text of the piece written by Adrian Furnham and published in the Sunday Times on 17th June under the heading “I’m sorry, he’s not a differently gifted worker – he’s a psycho”:

TWO things account for the success of a popular personality test: extensive marketing and the reassuring message you get with your results. Whatever profile you have, or type you are, “it’s OK”. We have different gifts. We can’t all be the same. Everyone is fine. Celebrate your quirkiness.

TWO things account for the success of a popular personality test: extensive marketing and the reassuring message you get with your results. Whatever profile you have, or type you are, “it’s OK”. We have different gifts. We can’t all be the same. Everyone is fine. Celebrate your quirkiness.

The message makes it easy for consultants and trainers. Researchers, however, know that one of the best predictors of success at work is (raw) intelligence, along with emotional stability and adjustment. But too many in the selection business are afraid of using well-proven tests to assess these factors for fear of having to deliver feedback such as: “Sorry you were unsuccessful in your application: the reason is that you are too dim and too neurotic.”

However, the message of “we are all OK” is not true. There are people with a distinctly unhealthy personality. There are many words for this. Some talk of “dark-side” traits, others of “abnormal” traits. And for more than 20 years, clinicians have talked about the maladaptive personality.

Researchers have recently tried to spell out traits that are most clearly manifest in the maladaptive personality. There are five of them.

Antagonism

This is defined as manifesting behaviours that put people at odds with others. It has components such as manipulativeness, deceitfulness, self-centredness, entitlement, superiority, attention-seeking and callousness.

Antagonistic people put everyone’s back up. They are selfish, self-centred and bad team players. The clever and attractive ones are the worst, because they use their skills and advantages to get what they want, come hell or high water.

Disinhibition

Defined as manifesting behaviours that lead to immediate gratification with no thought of the past or future. It has components such as irresponsibility (no honouring of obligations or commitments), impulsivity, sloppiness, distractability and risk-taking.

Think Kevin the Teenager. It can mean enjoying shocking others with unacceptable language, outlandish clothing or poor manners. This may be amusing in the playground but hardly acceptable in any form in the workplace.

Detachment

This is defined as showing behaviours associated with social avoidance and lack of emotion. It has various components, such as a preference for being alone, an inability to experience pleasure, depressivity and mild paranoia.

These are the cold fish of the commercial world. They seem uninterested in nearly everything and certainly the people around them. Some seem frightened by others, most just not interested in being part of a team.

Negative affect

This is defined as experiencing anxiety, depression, guilt, shame, anger and worry. It has components such as intense and unstable emotions, anxiety, constricted emotional expression, persistent anger and irritability, and submissiveness.

These are the neurotics of the world. They can be very tiring to engage with and highly unpredictable because of their mood swings. The glass is always empty, and they seem always on edge.

Psychoticism

This is about displaying odd, unusual and bizarre behaviours. It includes having many peculiar beliefs and experiences (telekinesis, hallucination-like events), eccentricity and odd thought processes. Some may see such people as creative, others as in need of therapy.

Psychiatrists have grouped those with personality disorders into three similar clusters: dramatic, emotional and erratic types; odd and eccentric types; and anxious and fearful types.

There are three important questions. The first is how you spot these people at selection so you can reject them. This is easier with some disorders than others. It is virtually impossible to spot the psychopath or the obsessive-compulsive person at an interview. Clearly, you need to question those who have worked with them in the past to get some sense of their pathology, which many are skilled at hiding.

The second is, given that they have already been appointed, how to manage them. There is, alas, no simple method that converts the antagonist into a warm, open, honest individual or the disinhibited worker into a careful, serious and dutiful employee. Sometimes it is a matter of damage limitation.

The third is how to rid your workplace of these maladaptive personalities, and that is the toughest question of all.

Adrian Furnham is professor of psychology at University College London and co-author of High Potential: How to Spot, Manage and Develop Talented People at Work (Bloomsbury)

.

.

.

…

Tags: advice, anxiety, depression, discrimination, law, Mental health, myths, OCD, prejudice, psychology, schizophrenia, stigma